Bungin Island, about two kilometres off the west coast of Sumbawa, has no reliable grid electricity, and communities are heavily dependent on small-scale fisheries.

Before solar-powered cold storage, fish often spoiled within hours due to heat, long travel times to markets and inconsistent ice supplies.

“We used to lose so much of the catch when markets were down or boats were delayed,” said Jayanthi Mandasari, a Bungin resident who runs the floating food stall with her husband. “Now we can keep fish fresh longer. It means income for our family.”

Bungin Island resident Jayanthi Mandasari runs a floating food stall with her husband, serving fresh seafood to locals and visitors. PHOTO: Jefri Tarigan

Australia Awards Short Course on Achieving a Just Energy Transition throughout Indonesia

The Australia Awards Short Course was designed to help Indonesian professionals plan and implement an inclusive, sustainable energy transition. Delivered by Griffith University and supported by KINETIK, it blended classroom learning with on-the-ground experience.

Adjunct Professor Paul Lucas, one of the course leaders, said the Sumbawa workshop demonstrated how the energy transition was being rolled out in Indonesia. “And that’s where the need is in remote and isolated communities.”

Course co-leader Professor Prasad Kaparaju stressed the importance of renewable energy being available outside of urban centres.

“Decentralised and remote energy development is essential if we want to achieve a just energy transition.”

“We don’t need handouts—we need technology”

The first field visit took participants to Pulau Bungin, home to more than 3,600 people from the Bajau seafaring community. Fishing sustains nearly every family here, but electricity capacity remains limited, and petrol access is costly. The community needs power not only for homes but also for nighttime fishing, when lights attract the most valuable catch.

Solar is slowly rewriting this story.

Six households now have rooftop solar systems. Even more transformative is a solar-powered cold storage facility developed by renewable energy startup Olat Maras Power at the University of Technology Sumbawa (UTS).

Nova Aryanto, a lecturer leading the initiative, said their work focuses on real needs:

“In Sumbawa, we have the highest solar irradiance in Indonesia. So why not use it to support people who depend on the sea?”

Before the cold storage was installed, fish that couldn’t be sold quickly would spoil or be dried at a much lower market value. Now, fishers here can keep their catch fresh overnight and sell when prices are better.

Bungin Village Head, Jaelani, sees this as more than an energy project:

“We don’t need handouts. We need technology that helps us work better. Solar keeps the lights on for fishing and helps us save what we catch.”

For Betti Ratekan, a short course participant from Bappeda Maluku, the visit resonated deeply.

“The energy transition must ensure justice and inclusivity, especially for Indigenous communities,” she said

From small islands to major industry

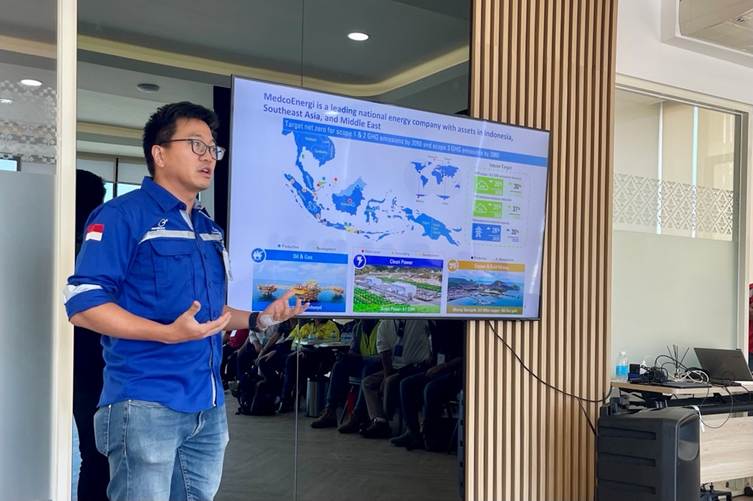

After Bungin, the group travelled along dramatic coastlines to the Medco Power Solar Sumbawa plant, one of Indonesia’s largest solar facilities dedicated to mining operations.

The solar plant, located in the Batu Hijau mining area, helps cut CO₂ emissions by around 40,000 tonnes per year while reducing the site’s electricity costs by up to 20 per cent. It has been jointly developed by Medco Power Indonesia and mining company Amman Mineral.

It forms part of Amman Mineral’s transition toward a cleaner energy mix. The company is also developing a 450 MW combined-cycle gas and steam power plant to further replace diesel and coal use.

“This integration of renewables into heavy industry shows that large-scale mining can contribute meaningfully to national emission goals,” said Adrianto Darmoyo, Vice President for Solar and Wind at Medco Power Indonesia.

As one participant noted: “It showed us industry can be part of the solution. The technology exists – what’s needed is leadership and collaboration.”

Participants as changemakers in their communities

Throughout the course, participants developed practical project proposals grounded in local needs and strengthened by lessons from Sumbawa, Australia and their diverse Indonesian regions.

Professor Lucas was impressed: “Each project had meaning, and each was relevant. A great cross-section of solutions.”

Examples included:

- Green Jobs for Women – led by Anggita Pradipta, Sun Energy

Anggita believes that gender equality must be embedded in Indonesia’s clean energy shift, not treated as an afterthought.

“There is huge potential for women to pursue careers in renewable energy.”

She added that women’s involvement is not only about fairness but also about unlocking national capability,

“We have the skills; what’s missing is opportunity. Renewable energy can open those doors, especially in regions where women’s livelihoods are more vulnerable.”

- Solar Irrigation for rain-fed Rice Farmers – joint project by Daniel Maynard Samosir from GIZ (the German Agency for International Cooperation) and Muhammad Nurdiansyah from PLN

This collaboration is aimed at supporting farmers who struggle with water scarcity and high fuel costs.

Daniel Mainard Samosir from GIZ and Muhammad Nurdiansyah from state-owned electricity company PLN are working together to pilot a solar-powered irrigation system in Sau Village, East Kupang Regency.

The pilot will replace existing diesel pumps with solar-powered water pumps, providing farmers with a cleaner, more affordable, and more reliable way to irrigate their rain-fed rice fields.

Kupang’s high solar irradiation makes it an ideal location for this project, which aims to demonstrate how renewable energy can enhance agricultural productivity while reducing emissions.

“If successful, we hope to replicate this model in other rice-producing regions facing similar challenges,” said Daniel. “We discovered that we shared a common understanding and decided to combine our ideas into a single joint project.”

- Legal framework for energy transition in Maluku — by Betti Ratekan (Bappeda Maluku – Provincial Development Planning Agency of Maluku)

For Betti, a just transition begins with policy that protects community rights.

She emphasised that strong legal backing is crucial to ensure that Maluku’s development plans genuinely advance energy justice, rather than remaining policy statements without enforcement.

Betti sees international partnerships as important to help realise the climate commitments outlined in the plan and ensure Maluku can drive a transition that benefits its communities.

“All of the projects have the potential for high local impact,” Professor Prasad said.

Building momentum beyond the course

Beyond new knowledge, the course created bonds.

“Participants are the future leaders of the energy sector,” said Professor Lucas. “They are forming the relationships to collaborate.”

Participants also highlighted the importance of continued collaboration beyond the course, including access to funding that would enable pilot projects to be rolled out in remote communities, stronger partnerships with local governments and industry and an active alumni network to maintain momentum and drive collective action.

“We’ll keep pushing to make these projects real,” Daniel said.

Looking Ahead

As the sun set over Sumbawa, participants reflected on the journey from policy debates to conversations with fishers whose future depends on accessible, reliable, clean energy.

Professor Kaparaju captured the essence of the program, “It’s about empowering people. From classrooms to coastlines to shape their own sustainable future.”

The course may have concluded beside the turquoise waters of Sumbawa, but its momentum continues through the alumni, determined to ensure Indonesia’s transition is not only clean but just.